The Puzzle Takes Shape

by Carl G. Karsch

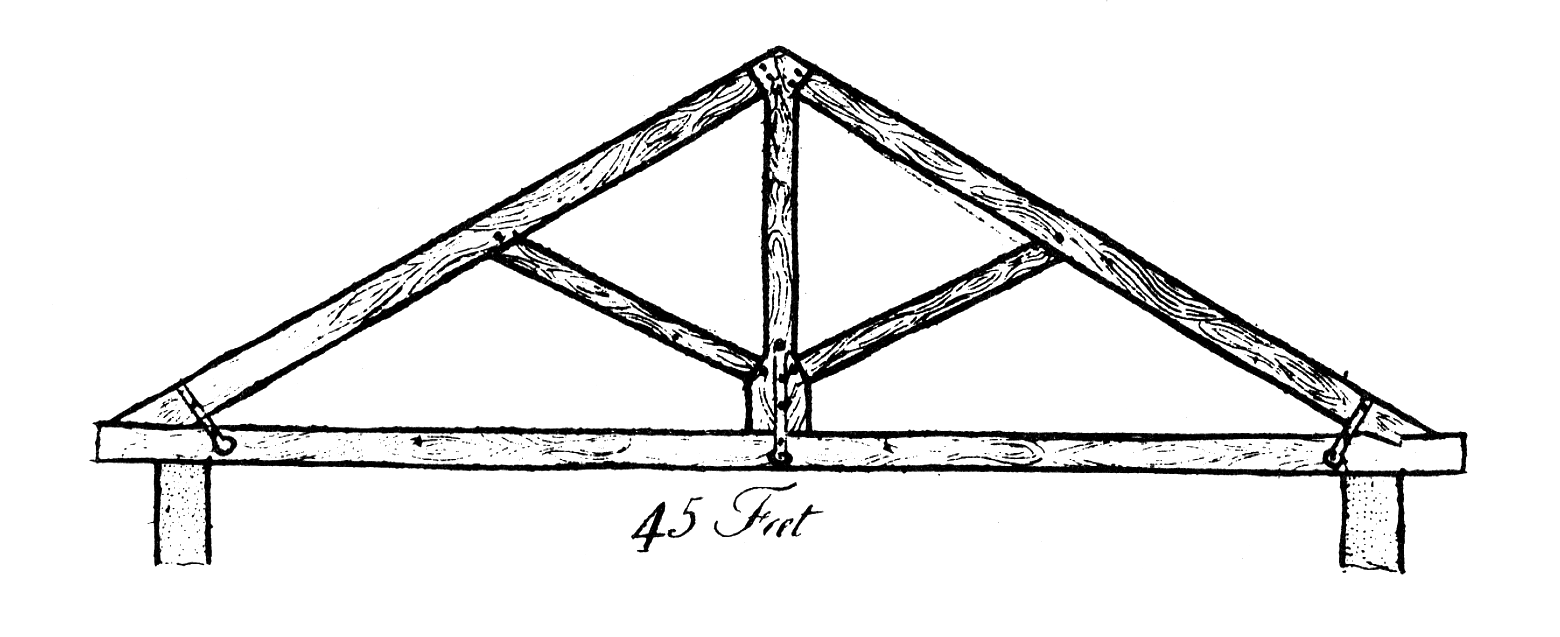

In 1980 restoration, steel beams were hoisted into the attic, then connected to support second floor trusses. Steel framework — installed in just five days — collected the load and transferred it to the strongest part of the building, the inside four corners.

If delegates to the First Continental Congress were to return, they would scarcely recognize where they convened on that sultry Monday morning, September 5, 1774. Except for the cupola, ball and weather vane, the Hall lacked the decorative finishing touches we take for granted. And for good reason. Construction costs stretched the budget to the point that Joseph Fox, one of the more prosperous members and also president, lent the Company 300 pounds just to complete the building. A fire insurance survey in 1773 summed up the interior appearance in two words: "very plain."

Delegates walked up wooden steps, over a wooden threshold, then through a doorway with nailing blocks set into unfinished brickwork to which a frontispiece would be attached 17 years later. Second floor windows lacked decorative balusters. Inside, partitions created an east room where the Congress convened, a west room and a passageway leading to a plain rear door and, in a cramped back yard, what were politely termed the "necessaries." The arch for the fanlight or "D" window would remain boarded over for 18 years. Fireplaces had only plaster surrounding the openings; chimney breasts were trimmed with corner boards and baseboards. Nothing more.

On the cover of the 1786 Rule Book is an engraving of the Hall from a drawing the late Charles E. Peterson believed Robert Smith probably presented at a meeting where his design was adopted. It shows a frontispiece different from the one actually constructed, three-sided steps at the entrance, and urns. Evidence of the intention for three-sided steps can still be seen in the exposed stonework at the south entrance. Smith never saw his dream realized. He became ill after working on river fortifications at Billingsport, NJ, and died at his south 2nd street home in February, 1777, six months before the British occupied the city.

Shoring tower supported second floor trusses while holes were drilled for hanger rods suspended from steel beams in the attic. System was designed by Nicholas L. Gianopulos, drawing on work he did earlier in Park buildings.

On the second floor, delegates had permission from the Library Company, the Hall's first major tenant, to borrow books for reference and whatever leisure they enjoyed. The stairway to the second floor is thought to be original, except for the wainscoting. Lining the walls of what is now the Dalkeith room were carved wooden cabinets, bookshelves protected with wire lattice and inside shutters, all built by Thomas Nevell. In his home on south 4th street Nevell opened the city's first architecture school. His other achievement: Mount Pleasant, a masterpiece mansion in Fairmount Park where Benedict Arnold and his bride, Peggy Shippen, once lived.

It's now 1790, the new national government is moving to Philadelphia. Office space is at a premium. The Company, to attract prospective tenants, voted not only to complete their "Old Hall" — but to create additional rental space, erect "New Hall." Within a year, the frontispiece frames the entrance, balusters grace the second floor windows, and the court is paved. New cedar posts support the wooden steps. Granite steps would have to wait another fifty years.

New Hall was barely under roof before General Knox, the first secretary of war, became a reluctant tenant. He had been displaced from his freshly wallpapered and painted west room of the Hall by a well-heeled tenant, the First Bank of the United States. An advance of one year's rent by the bank helped pay for the recent flurry of construction and make possible, finally, the rear frontispiece and fanlight. William Linnard, who later became commandant of Fort Mifflin and quartermaster general of the army, was in charge of fabricating and installing the frontispiece. Again, granite steps would be postponed, this time till the major restoration of 1857. First floor partitions were removed, perhaps at the bank's request.

Compiling a building's history resembles a jig-saw puzzle. With an historic building such as Carpenter's Hall, pieces of the puzzle are to be found in documents of many kinds as well as in the fabric of the structure itself. But identifying the pieces is only the beginning. In the case of the Hall, it took a team of historians, architects and researchers from other institutions — pooling their information — to begin assembling the puzzle. But as with any puzzle, pieces may be missing.

The team to which we are most indebted includes:

- Charles E. Peterson, architect and Company member, whose research is fundamental to understanding the Hall.

- Beatrice H. Kirkbride, of the Philadelphia Historical Commission. Her report examined changes in appearance of the south doorway during the 18th century.

- G. Edwin Brumbaugh, an architectural consultant who authenticated dates and construction of the south doorway's frontispiece and fanlight or "D" window.

- Lee H. Nelson, Park Service architect. His study revealed not only details of the original fireplaces but also the adaptive re-use of the 18th century wood flooring. He also verified earlier studies of the south doorway.

- Penelope Hartshorne Batcheler, historical architect, now retired from the Park Service, worked with Nelson and later on other projects.

Fireplaces then & now. Nearly 40 years ago the Company decided to re-open the first floor fireplaces and install today's decorative mantelpieces. The rationale: this is how the Company would have dressed up the fireplaces in 1773, had money been available. Fortunately, Nelson and Batcheler were called in to examine the openings, sealed a century earlier with the installation of central heat. Their discoveries:

- Despite many stovepipe holes in the chimney breasts to accommodate a succession of stoves, the masonry backs of the fireplaces are original.

- While researching buildings in the Park, Mrs. Batcheler perfected a means of helping date construction by examining, under a microscope, multiple layers of paint. This technique also lays bare the entire chronology of plaster wall paint colors. At the chimney breasts the initial layer is cream; later layers are mostly white, except for bright yellow near the surface. There are also vestiges of wallpaper.

John F. Harbeson won a Company-wide design competition for the new fireplaces. He and Thomas S. Keefer, charged with the project, agreed to stilt out the new trim, thus preserving the original plaster and simple openings for future study.

Old & older. While studying the fireplaces, the pair of Park architects laid bare a striking example of 19th century thrift. The original random width yellow pine flooring — in place for more than a century — had been cut into short lengths and placed on legers to span between the floor joists, thus supporting beds of grout for the tile floor. (A successor company to Minton at Stoke-on-Trent, which in 1870 made the first tiles, provided replicas for the 1980 restoration.)

Inside the cellar door are two windows with the original half-round jamb molding. Where that molding abuts the partition, more elaborate trim begins, continuing throughout the first floor. Mrs. Batcheler believes the later trim dates from the 1870 restoration.

Another discovery. On pilasters inside the decorative columns on the first floor there is evidence of where the early partitions were attached.

Tree ring tales. Some of the white oak trusses in the Hall's attic were saplings 20 years before William Penn came ashore at Dock Creek. At Old Swede's Church, the region's oldest large structure, timber from some of the trusses is dated to the decade before Columbus landed in America. How can we be sure? A team led by Mrs. Batcheler took core samples from trusses in nine buildings, including the Hall and Old Swede's Church, with known construction dates from 1700 to 1828. At Columbia University's tree ring laboratory, the cores were cross-referenced and correlated with data from other areas on the mid-Atlantic seaboard. The resulting dendrochronology database now helps date buildings where construction dates are uncertain.

On display. For Queen Elizabeth's visit in 1976, Mrs. Batcheler and her husband, George, a Company member, created a display including the Hall's most prized possession — copperplate engravings of the 1786 Rule Book — and a silver tankard dated 1724 given by the Worshipful Company of Carpenters of London. Later, they consulted with craftsmen from Wilmington's Hagley Museum, who worked from measured drawings to build the eye-catching model of the Hall under construction.

"See What They Sawed." This was the title given an exhibit funded by the Company to celebrate its 250th birthday. On display in the First Bank were dozens of items from the Park's architectural study collection: 18th century doors, chimney breast paneling, mantlepieces, a winding stair, shutters, cornices and hardware. Charles Peterson began amassing the collection in the early 1950's to illustrate how 18th century buildings were put together. Later, Mrs. Batcheler and summer students salvaged key portions of buildings about to be demolished. Today, this unique collection, completely catalogued, reposes in the First Bank's basement, behind impressive iron doors which once guarded the nation's gold. Visitors are welcome by appointment with Park curators and architects.

Shards in the attic. Clues to the past, whether of families or the Company, are most likely found in the attic. Such was the case in 1980, during the most recent restoration. Beneath layers of 18th century dust Mrs. Batcheler found hand-dressed cedar shakes three feet in length, most likely from the Hall's first roof. From other hiding spots she assembled a boxful of objects, now catalogued, including: early examples of bricks, laths and glass.