Following the Money

by Carl G. Karsch

Continental currency bears signatures of Levi Budd, a Company member who contributed to building the Hall, and Thomas Coats, his partner in a lumber business on north Front St. Paper money was individually signed by prominent citizens to reduce counterfeiting. Nine Company members signed issues of either Pennsylvania or Continental currency. Hall and Sellers' print shop was on Market St. across from Franklin Court. Plates were engraved under military guard at a secret location.

General Washington, the only commander-in-chief who could afford to serve without pay, needed an accountant. "I do not wish to make any profit... [but] I will keep an exact account of my expenses. These I doubt not they [Congress] will discharge."

Conrad Bartling, who signed the Company Articles in 1785, helped build the first U.S. Mint near Seventh & Arch Sts., two blocks west of the present mint. A skilled carpenter, "measurer" of other men's carpentry and chief inspector of lumber, Bartling spent his last 15 years as the Hall's superintendent. (courtesy: The Free Library of Philadelphia)

Sounds simple. In fact, Washington faced a bookkeeping nightmare. Each state issued paper money which also circulated in neighboring states at varying rates. Then there was Continental paper currency backed by nothing but a pittance of funds in the treasury. As the Revolution dragged on, all paper money lost value — and inflation skyrocketed. Washington began his accounts with Pennsylvania money, then switched to that of New York while fighting in New England, and finally to Continental dollars. After the war, before Congress would accept his bills, Washington had to arrive at a bottom line taking into account years of devaluation and inflation. No doubt he lost money. But then his soldiers had to threaten more than one revolt just to receive any back pay — in nearly worthless paper money. Franklin, in one of his less charitable comments, called the financial chaos a tax to pay for the Revolution.

Americans never wanted paper money but in the western world became the first to use it. To keep her colonies subservient, England refused immigrants permission to bring coins, known technically as "specie." Worse, the royal postal system demanded payment in hard money, a constant drain on colonial treasuries. Merchants bought and sold ships' cargoes with letters of credit, a form of paper money.

Coins of every European power found their way into America via trade with possessions in the West Indies. There were coins of Dutch, French, British, and Portuguese origin. Most abundant: Spanish silver reals (royals) minted in Mexico. All varied in quality and could be clipped, filed and chipped. Traders had to use scales to determine a coin's value. The basic Spanish coin, the "real," or dollar as Americans called it, had grooved or "milled" edges to discourage clipping.

Instead of our current decimal system of pennies, nickels, dimes and quarters, the Spanish real was divided into eighths, with five coins of varying combinations. Before the Revolution, many states protested British domination by replacing pounds, shillings and pence with the Spanish monetary system. At least in theory, Continental paper money could be redeemed for Spanish milled dollars. The Spanish system of eighths of a dollar became so embedded that it wasn't till 1998 that the stock exchange took the bold step of valuing fractions of shares in tenths.

Death to Counterfeiters. Neither this warning printed on some paper money nor threats of branding, ear-cropping or whipping stopped production of fake currency. First to suffer was Indian tribal wampum, shells cut into circles, polished and strung. Rare purple shells were worth five white ones. Early settlers, who used wampum and barter to settle accounts, learned how to dye white shells. Colonists could be fooled; Indians weren't.

To deter counterfeiters, some paper bills contained blue silk threads or flecks of mica. Nothing worked. Genuine currency often was artistically crude and poorly printed. Bills that were torn, soiled or patched were hard to detect. Congress, desperate to improve bills' quality, hired a skilled engraver who had served time as an equally talented counterfeiter.

The British occupying New York added to wartime inflation by trying to flood neighboring states with well crafted fakes.

New Coins for a New Nation. For an expanding nation, the complex brew of foreign coins became distasteful. In 1792, eleven years after Yorktown, Congress authorized its first structure — the U.S. Mint. Purpose: to manufacture gold, silver and copper coins of uniform quality in the decimal system. Not an easy task. Engravers and mechanics had to perfect techniques of metallurgy, precision tools and scales to maintain quality. The first sources of power for the mint were horses to drive the rolling mills and men stamping coins with a heavy screw press. Fortunately, David Rittenhouse became the mint's first director. Scientist, astronomer, inventor and builder of fine clocks, Rittenhouse understood precision machinery. Two decades earlier he built the first practical planetarium which, using clockwork, could display rotation of planets in the solar system for a period of 10,000 years. His "orrery," housed in a mahogany case with a glass front, is at the Van Pelt Library of the University of Pennsylvania, where he was the first astronomy professor. Not until 1933 would Philadelphians see a successor — the auditorium-sized Fels planetarium at the Franklin Institute.

Faced with glistening marble, the Bank of Pennsylvania met in Carpenters' Hall while its new home took shape on south 2nd St. Above is the City Tavern, built by Company member Thomas Procter. (courtesy: Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

The demand for coins proved insatiable. So acute was the shortage that legislation withdrawing foreign coins after 1795 had to be extended three times. Last to cease being legal tender — six decades after the mint's founding — was (you guessed it) the Spanish milled dollar.

Cornering the Market on Banks. Carpenters' Hall, the colonial city's major rental building, became a hot property for at least a score of new organizations. Four banks called the Hall home while awaiting larger quarters. Here are their stories.

The Bank of Pennsylvania. Charleston fell to the British in May, 1780, the nation's largest single defeat. Lost was the largest city south of Philadelphia, 5,400 Continental soldiers taken captive, and — worst of all — arms and provisions for the southern campaign. American finances were at the breaking point. New arms and supplies seemed unlikely. With the Revolution facing collapse, Philadelphia's wealthy merchants moved quickly. In less than a month they created a short-term lending institution, the Bank of Pennsylvania, and pledged their entire capital of 300,000 pounds. A total of 1,645 women, not to be eclipsed, raised an equal amount in paper money and hard currency. Contributors ranged from a black servant named Phillis (7 shillings, 6 pence) to Madame de Lafayette (100 guineas sterling) and the Countess de Luzerne, wife of the French ambassador, (6,000 dollars in paper money and 150 dollars in specie). Washington, touched by the women's generosity, recommended donations be deposited in the newly created bank, which made possible the campaign leading to victory at Yorktown.

Company members George Watson and his son, George Jr., built the third structure of the Bank of North America, on Chestnut St., just west of 3rd. In 1872, the Watsons erected College Hall, the first building on the University of Pennsylvania's new West Philadelphia campus. (courtesy: The Free Library of Philadelphia)

Seventeen years later the bank decided to replace its home on 2nd St. just north of the City Tavern with a striking marble edifice. For two years the first floor of Carpenters' Hall became the Bank of Pennsylvania. Both gained notoriety as the site of the 18th century's largest bank robbery, which took place during the yellow fever epidemic of 1798. (See:America's First Bank Robbery). September, 1857, also proved memorable. A financial panic swept the country, bringing down the Bank of Pennsylvania. And on September 5 — the 83rd anniversary of the First Continental Congress — the Carpenters' Company celebrated their return from New Hall to the refurbished original building.

The bank housed prisoners during the Civil War before demolition in 1867.

The Bank of North America. Early in 1781, with Yorktown eight months distant, the country faced financial disaster. To pay its bills, Congress had no choice but to keep issuing paper currency, which depreciated in value almost as quickly as it left the printer. Robert Morris — wealthy Philadelphia patriot and a founder of the Bank of Pennsylvania — had personally supplied funds more than once to keep Washington's army fighting. Now he faced a tougher job. Congress appointed him superintendent of finance, a new office, to restore faith in America's credit and currency. His solution: the Bank of North America which fulfilled its expectations — and even turned a profit. A mill in suburban Merion produced bank note paper with a marbled background to deter counterfeiting. The bank had a close call in 1783. Soldiers mustered out without pay after the British finally sailed from New York threatened to storm the building, on the north side of Chestnut St. just west of 3rd.

On its tenth anniversary the bank moved to Carpenters' Hall for two years while a new building was underway at the Chestnut St. site. That year (1791) the bank honored the new Mint by changing from pounds, shillings and pence to the present decimal system. George Watson and his son, both Company members, were contractors for the bank's third home, also built at the same location. In 1929 at the onset of the Great Depression, the Bank of North America was merged out of existence, although the building survived until 1972.

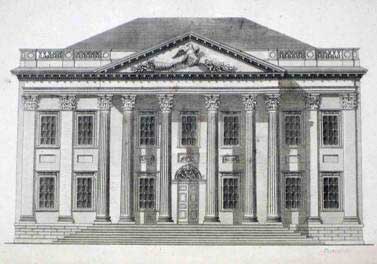

Owen Biddle's meticulous elevation of the Bank of the United States is one of 44 plates in his landmark book, "The Young Carpenter's Assistant." In 1804, two years before his death at age 32, Biddle proposed a novel idea to the Company — a school to teach architecture. A committee studied the plan, distributed copies to the membership, which at a special meeting voted it down.

Bank of the United States. Alexander Hamilton's financial genius — a unified coinage backed by a national bank — became reality in 1791. Chartered by Congress in February, the bank in December moved into the west room of Carpenters' Hall, recently vacated by General Henry Knox, the first secretary of war. The Bank of North America, however, remained in the east room for a year and a half. Then the First Bank (as it became known) signed a lease for the entire first floor.

Fire nearly consumed the Hall in May, 1793, the year of the most serious yellow fever epidemic. Flames broke out in frame houses on the west side of Third St. — the bank's future location — and spread quickly to shops of a gun manufacturer, carriage maker and, ironically, a builder of fire engines. A newspaper reported: "The Bank of the United States was in imminent danger... but preserved by the incessant discharge of water from the engines."

Bank directors moved quickly. They began negotiations to purchase the now vacant lots on Third St. and insisted on construction of a brick "fireproof " adjoining the Hall in the northeast corner. This ungainly addition survived 75 years and served two later banks.

Main banking room of the Second Bank of the United States, pictured after it served as U.S. Customs House. Master carpenter was Philip Justus. Born in 1770 — the year construction began on Carpenters' Hall — Justus lived till 1861, the year Fort Sumter was fired upon. (courtesy: Independence National Historical Park)

Second Bank of the U.S. Stephen Girard, whose multi-million dollar will funded Girard College, at first lived above his waterfront warehouse just north of the present Ben Franklin bridge. By 1811, when the First Bank's charter expired, the fortune amassed by Girard's fleet of ships enabled him to purchase the building, rebuild the interior to his taste and establish a bank bearing his name. Perfect timing. Girard's bank became the principal source of credit for Congress during the War of 1812. Later he personally underwrote 95 percent of the war loan. It's hardly surprising that when in 1816 Congress chartered the Second Bank of the U.S., Girard became a director.

With no place to call home, the Second Bank rented Carpenters' Hall for five years while its future residence took shape one block west. (See Houses for Ships. Sailors, Music and Money.) Twenty years later, the bank's charter having expired, the building became the U.S. customs house, where it resided until the current headquarters were completed in 1933. Earlier, for 16 years, customs house employees came to work at — where else — Carpenters' Hall.