Houses for Ships, Sailors, Music & Money

courtesy: The Free Library of Philadelphia

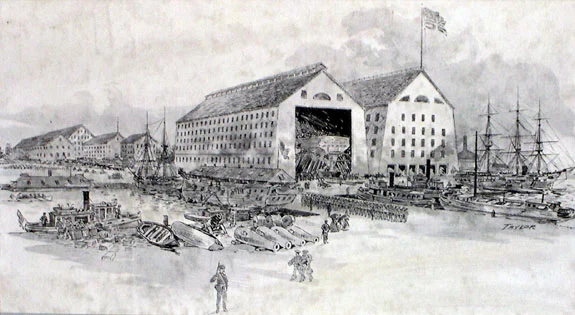

After a century or more of service, can a building be successfully recycled? Or is demolition its only fate? Philadelphia has suffered more than its share of the latter. But a surprising number of factories, office buildings and even churches — many by Company members — have found new lives, continuing to contribute their distinctive architecture to the urban scene. Here are three examples. Unfortunately, the shiphouses disappeared before waterfront condos became popular.

1821 – Of the thousands of structures designed or built by Company members, the pair of wooden shiphouses Philip Justus completed for the nation's first naval shipyard are unique. Their purpose: to shield shipways, vessels under construction and craftsmen from severe weather. In this Civil War era illustration, the shiphouses — waterfront landmarks for nearly a half-century — near the end of their lifespan. Warships of iron and steel would be constructed farther downriver, at the confluence with the Schuylkill river. Today, a Coast Guard facility just south of Washington Ave. has replaced the first naval shipyard.

Philip Justus (elected 1801; deceased 1861) in his 91 years witnessed the country from its early years till the Civil War. He was versatility personified. Four major buildings are identified with him. Justus also built houses and in later years surveyed them for the Mutual Insurance Company. One was the Graff House, where Jefferson penned the Declaration of Independence. Justus was a county commissioner and treasurer of a mining company. For much of his adult life, he is listed modestly in city directories as "carpenter, 24 Wood St.," near the waterfront, just north of the present Benjamin Franklin bridge.

In 1816, five years before his shipyard contract, Justus earned his engineering credentials. Washington Hall, an auditorium with the incredible seating capacity of 6,000, was underway north of Third and Spruce Sts. Designing the roof fell to Justus. Five years later, when he was working on the first shiphouse, Washington Hall burned.

courtesy: The Free Library of Philadelphia

1824 — The Second Bank of the United States, one of the first public buildings in the Greek revival style, became the architectural and financial centerpiece for the city's 19th century banking district. Architect was William Strickland; Philip Justus the superintendent of carpenters. His contract included additional payment for hoisting machinery; mahogany desks, doors and mantels; shingling the watch house and the indispensable privies.

Like its predecessor, Alexander Hamilton's First Bank of the United States, the Second Bank transacted business in Carpenters' Hall while the future home was underway several hundred feet to the west on Chestnut St. Until its demise in 1832, the Second Bank made Philadelphia the nation's financial capital. All that changed when President Andrew Jackson vetoed renewal of the bank's charter and withdrew federal deposits. A hero of the Battle of New Orleans, Jackson was at heart a frontiersman who mistrusted eastern bankers and would have preferred hard currency in his pocket to paper.

Beginning in 1844 and for the next 91 years, the Second Bank served as Philadelphia's Customs House. Earlier, this institution, too, did business in Carpenters' Hall. Now the Second Bank houses the Portrait Gallery of Independence Park. Included in its unparalleled collection of paintings of America's founders is a bust of Nicholas Biddle, president of the Second Bank of the United States.

1824 – With Musical Fund Hall, the city gained center stage culturally and politically. Nearly perfect acoustics made the Hall the favorite venue for concerts and operas through the Civil War and until the Academy of Music's debut in 1857. Jenny Lind, known as the "Swedish Nightingale," thrilled audiences. The first American performance of Mozart's "The Magic Flute" was staged here.

In 1856, the newly formed Republican Party held its first convention in the Hall. The illustration depicts a spokesman proclaiming the party's nominee, John C. Fremont, called "The Pathfinder" for his exploration of the West. Fremont failed, however, to find the path to the White House. James Buchanan, of Lancaster, PA, won the election handily.

The Musical Fund Society received its charter in 1820 "to cultivate musical taste and assist needy musicians and their families." Lacking a meeting place, the Society rented the first floor of Carpenters' Hall for concerts and instruction in music. Four years later they hired architect William Strickland to remodel a church on Locust St. west of Eighth. The builder: John O'Neill (elected 1809; deceased 1835). O'Neill, father of two sons who also became members, served the Company in many capacities: the Managing Committee for 17 years; the Committee on the Book of Prices for 19 years; also as warden and secretary. He died while vice president. O'Neill is remembered for Musical Fund Hall and the U.S. Naval Home (below). Both are now condominiums.

courtesy: The Free Library of Philadelphia

1833 – At 24th St. and Gray's Ferry Ave. — beside the historic road Washington traveled to Philadelphia — William Strickland and John O'Neill again collaborated. Their impressive project had a name to match: the U.S. Naval Asylum and Hospital, later simplified to The Naval Home, which survived till 1976. Biddle Hall, the central structure, had 400 individual rooms for ill or retired veterans. Each opened onto verandas running the length of the building. The fireproof design incorporated an early use of cast iron as a building material.

For six years (1839-1845) veterans shared Biddle Hall with the first naval academy. Navy secretary George Bancroft then moved the school to "the healthy and secluded" location in Annapolis, MD, to remove midshipmen from "the temptations and distractions that necessarily connect with a large and populous city." Apparently, veterans at the Naval Home were considered immune.

C.G.K.